Protect and Expand Healthcare Coverage for All Virginians

Prior to the passage of the Affordable Care and Patient Protection Act (ACA) in 2010, there were about one million uninsured people in Virginia and 50 million nationwide. Because of the ACA, the number dropped to approximately 750,000 statewide and 28.5 million nationally in 2015 and would have improved a lot more if the remaining 19 states, including Virginia, had expanded healthcare. The ACA not only expanded coverage but put in place important protections for consumers including:

- Those with pre-existing conditions can’t be charged more or denied coverage.

- Women can’t be charged more than men,

- Insurance companies couldn’t impose lifetime caps, and

- Children under 26 years of age can stay on their parent’s health insurance.

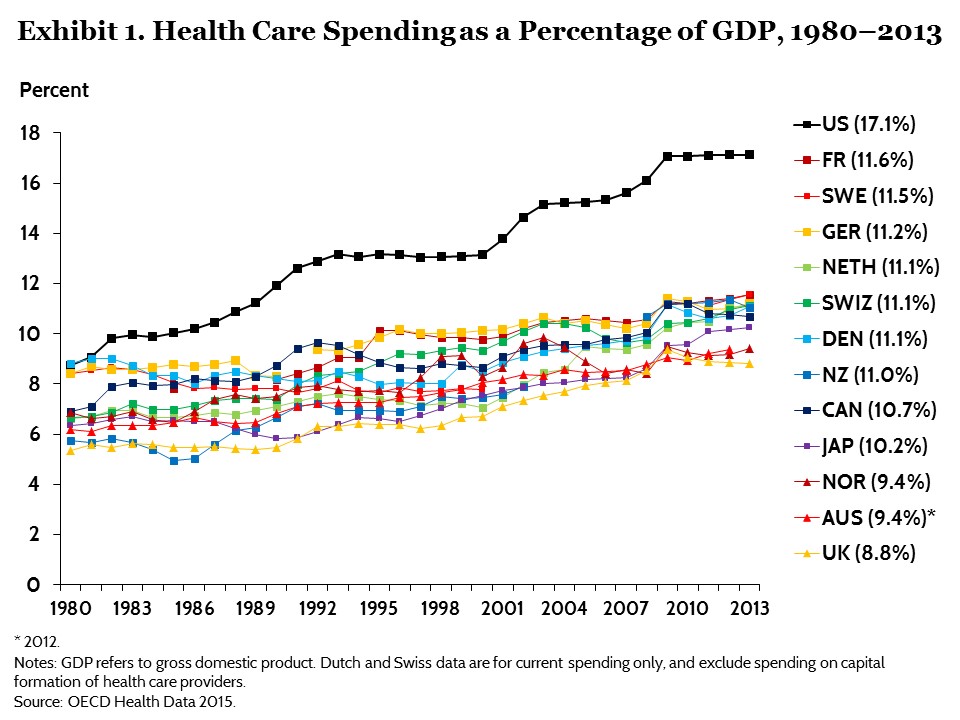

United States healthcare costs are the highest in the world, and yet the U.S. has the lowest average life expectancy compared to economic peer nations.

The ACA’s requirement that insurance not exclude people with pre-existing conditions and premiums be community rated was a major change to the health insurance marketplace. Since insurance companies must retain a balance mixed of healthy and sick people for insurance to work, this was to be offset by a mandate requiring all individuals to be insured, as well as the development of a Federal Marketplace to help individuals purchase health insurance, including provisions to provide additional help to companies that initially enrolled an imbalance between high and low cost participants. Congress, however, did not appropriate the money, to compensate for this adverse risk, which was authorized in the law resulting in these companies having to bear the loss alone. As a result, some of them either dropped out of the individual market or raised their premiums by large amounts.

As a result of the implementation of the Affordable Care Act, almost 380,000 Virginians receive healthcare coverage through the Federal Marketplace and 84 percent, 319,000, receive federal tax credits to offset the cost of premiums. About 220,000 of those receiving tax credits also receive additional subsidies for cost sharing because they have incomes under 250% of the Federal Poverty Level (FPL), less than $50,400 for a family of three.

Virginia also has about 1.4 million people, or approximately 16 percent of its population, who receive healthcare coverage through Medicaid/FAMIS. More than three-quarters of these Medicaid/FAMIS recipients are children with average annual cost of a little more than $2,000 annually. Aged and disabled persons represent less than a quarter of Medicaid recipients but cost an average of more than $17,000 annually.

Because Virginia did not take advantage of the ACA that allow states to pull down federal dollars for expansion, Virginia also has about 400,000 people who are uninsured and have household income of less than 138% of the Federal Poverty Level, about $16,000 for an individual or $27,000 for a family of three. Most of these residents are employed or family members of people employed. These people remain without insurance coverage because Virginia hasn’t taken the federal dollars available for expanded coverage.

Medicaid expenditures have been increasing nationally due to growth in our aging and disabled populations and continual growth in health care expenditures. It is important to note that States that expanded coverage saw their Medicaid expenses increase at a slower rate than states that didn’t. This may only get worse if Virginia doesn’t figure out a way to provide healthcare coverage for the significant number of uninsured, low-income people in the state. People who go without the regular primary and preventative services that coverage affords are more likely to become disabled at an earlier age and, when they do become eligible for Medicare and Medicaid (if low income) at 65, they are sicker and require more resources.

- Congress passed a reconciliation bill this past year that was vetoed by President Obama which would have limited future Federal Medicaid funding by eliminating money available to states for expansion and giving the states an option of receiving a fixed “block grant” or “per capita” amount (based on current Medicaid enrollees and some estimate of state costs) with any increase tied to general inflation, not healthcare cost inflation. The amount would not be adjusted to account for increased need due to an aging population, an economic downturn, continued growth of healthcare costs above inflation, or other factors beyond the control of state governments. The only real “flexibility” a Medicaid block grant would give states is the flexibility to decide how to make up Medicaid funding shortfalls (e.g. services to cut, which provider payments to cut, which taxes to raise, etc.). Because of Virginia’s relatively low Medicaid cost and enrollment currently, it will be particularly hard for our state to respond to the healthcare needs of vulnerable Virginians with a change in the federal funding mechanism.

The ACA added several new benefits to Medicare such as a new array of preventive benefits, a new annual wellness benefit, legislation to close the “donut” hole in Medicare Part D, and several new steps to slow down costs by moving to outcome based payments. These changes reduced out of pocket costs for beneficiaries and extended the solvency of the Part A trust fund by almost 12 years. Contrary to what has been stated recently, the ACA has improved the solvency of Medicare. The repeal of the ACA would leave all of these provisions up in the air.

- House Speaker Paul Ryan is on record saying that he wants to abandon the social insurance principles of Medicare and privatize it through a plan called “premium support.” This essentially gives vouchers to seniors who will then buy their health insurance in the private market. Every reputable analyst has concluded that this would drastically increase out of pocket costs for seniors possibly costing some seniors as much as half their social security income annually.

What can Virginia do to protect and expand healthcare access?

Take advantage of every Federal dollar that becomes available for improved access.

- With the potential repeal of the Affordable Care Act and change in federal Medicaid funding, Virginia cannot afford to be one of the 19 states left behind. We need to ensure we are able to maximize how much money we can bring back to Virginia to protect our communities and healthcare providers, to provide health care to thousands of hardworking Virginians, and to create jobs and stimulate the economy.

Any proposed changes in funding of Medicaid and other federal healthcare programs need to be carefully evaluated to determine long-term impact on Virginians access to needed services, particularly for low-income and vulnerable populations.

- Block grants and similar programs that limit federal responsibility for care of vulnerable populations only push the responsibility onto Virginia lawmakers and its citizens. Moreover, the federal government’s ability to take on debt during economic downturns is not shared by Virginia and, therefore, has far reaching implications for our state’s economy.

Support the work of Virginia’s Joint Subcommittee on Mental Health to address access to and coordination of critical behavioral health services.

Untreated behavioral health conditions have far reaching impacts on our communities, economy and the individuals and their families with mental health/substance abuse. Virginia has made some progress with the implementation of the GAP (Governor’s Access Plan) Medicaid waiver program and its ARTS (addiction & recovery treatment services) waiver amendment to add improved treatment for Medicaid recipients (expected to begin April 2017), however, the opioid crisis and limited access to community based services statewide have created strain on our criminal justice, healthcare, and economic development systems. The Joint Subcommittee is studying and is expected to develop recommendations to address these impacts.

- The Virginia Interfaith Center supports the work of mental health advocates throughout the state. Some of the priorities for mental health advocates are:

- Timely, appropriate, affordable services as early as possible;

- Eliminate waiting lists through “same day access” throughout the state;

- Integrate health and mental health services in the community; and

- Support jail diversion for people accused of crimes for whom voluntary mental health or substance use treatment is a reasonable alternative to confinement.