By Dora Muhammad, Congregation Engagement Director —

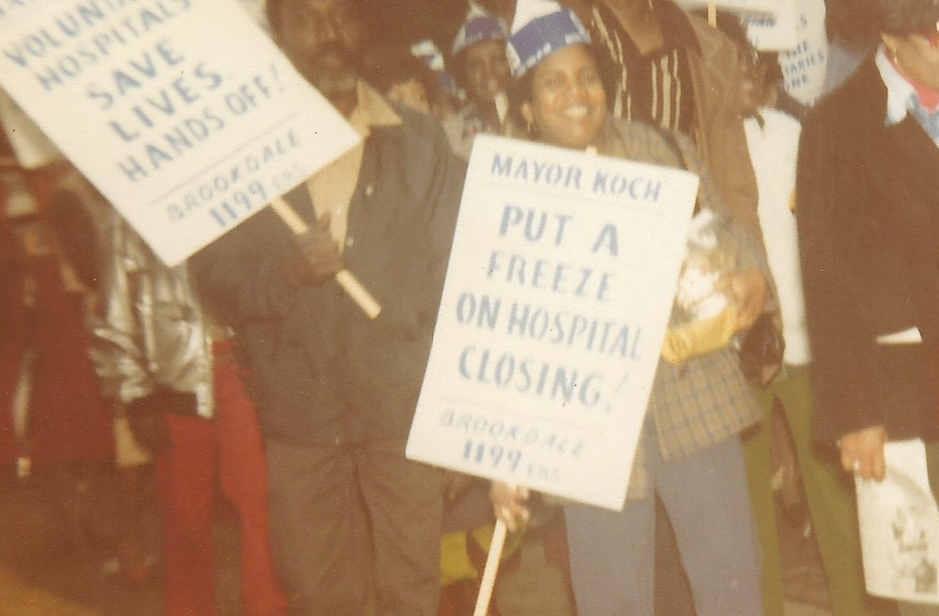

Photo: My mother at a 1984 union protest in front of Mt. Sinai Hospital in New York —

In early April when the Centers for Disease Control released its first snapshot of demographic data in COVID-19 cases, alarm bells rang across the country over the wide racial disparities. Black people were being hospitalized and dying at higher rates than any other race; and at significantly disproportionate ratios when compared to their percentage of the population.

The bells have not stopped ringing. They are sounding louder every day as more people are looking through the magnifying glass that COVID-19 has held steady over the health inequities in this country. And they vibrated through my cell phone nearly daily throughout the entire month of April.

Even though I oversee Virginia Interfaith’s health equity work, the pandemic’s impact has been overwhelmingly personal. I have received steady notifications about COVID-19 deaths of family members, childhood friends and members of their families, past and current colleagues, mentors, and personal associates. My personal tally today is more than 75 deaths.

I was born and raised in New York. My mother, a Caribbean immigrant, began working at Mt. Sinai Hospital in 1975 in housekeeping and eventually became a trainer of its cleaning staff. In 1981, she became a unit clerk and worked in that capacity until 1989. My entire childhood, my mom was a frontline health care worker as part of NYC’s 1199 union. I inherited many things from her—and this pandemic has reminded me that health equity advocacy is one of them.

While I am blessed with the capacity to work remotely from home, I reflect on my mom as I pray for all of today’s essential workers who do not have this capability during the pandemic. This circumstance is one of the major factors that has led to so many COVID-19 deaths of people of color. How outrageous was it for the U.S. Surgeon General Jerome Adams to say at a White House press briefing on April 13, that we are “socially predisposed to coronavirus exposure.”

Surgeon General Adams seemed to believe he was delivering a culturally tailored message to Black and Brown communities during that briefing. Amid listing CDC recommendations of social distancing and frequent hand-washing, he called on us to “step up” and “avoid alcohol, tobacco, and drugs” to help stop the spread of COVID. So, I questioned whether he had a skewed understanding of the social determinants of health when he mentioned alcohol, tobacco, and drugs.

Health inequities prevail more significantly as a result of social determinants than clinical determinants. The World Health Organization defines these factors as “the conditions in which people are born, grow, live, work and age. These circumstances are shaped by the distribution of money, power and resources at global, national and local levels.” The poor health outcomes in the Black community rests in employment opportunities, access to health care and resources, early childhood development and education, housing and the built environment—and the historic exclusion of Black people in the systems that govern and administer these sectors of society.

Ever since the first enslaved Africans survived the Middle Passage to reach the shores of this country in 1619, our health outcomes have been at the bottom of an abyss. The time is long overdue to address the health implications of racism. The world is watching and waiting to see if this country will have the courage to take this step.